The Peterloo Massacre - Manchester 16th August 1819

Rowbottom's Comments on Trade and Politics - 1800 to 1819

As Recorded in the Diary of William Rowbottom

Comments and additional information (in italics) are from the transcription by Samuel Andrew,

serialised in the 'Oldham Standard' between 1887 & 1889

Cost of Provisions HERE

1799 (for Background)

January 31st – The frost still continues with unabating severity, and yesterday it was an uncommon day of wind and snow, and this morning it was most tremendosley roof.

January 31st – The frost still continues with unabating severity, and yesterday it was an uncommon day of wind and snow, and this morning it was most tremendosley roof.

The fustian trade continues very bad, and the frost and snow being so against the poor, it makes their situation the more deploreable; for, indeed, at this time they are the most miserable beings upon earth.

It was within a decade of this time that Joseph Bently’s family were engaged in cotton fustian weaving by hand. The trade fluctuated a great deal, and was sometimes better and sometimes worse. He draws a pretty picture of the life of a child in those days:“

For more than a year”, says Joseph Bently, in his ‘Gems of Biography’, “my life was passed in …. Frequently taking granny’s position at the wheel in winding bobbins for father and mother. When I was nearly six and a half years old, however, all this was changed. A pair of looms was bought, and I was actually set to weave strong fustian at that early age – earlier than ever I knew any one put into the loom in any part of the country. My work at first was to weave a yard and a quarter of strong velveteen fustian daily. My little arms were so short that a long handle was screwed to the lathe for me to move it by, and big lumps of wood were nailed on the six traddles to compensate for the shortness of my legs. I was thus set to make cloth for other people’s garments, that I might earn my own bread. Though many persons expressed serious doubts whether I should be able to bear my work, it did not seem to injure me, as I continued growing pretty well and I was a tall boy for my age. Of course, few people took much notice of the neglected state of my mind, or thought of the wrong done to the moral and intellectual nature. These things were lightly esteemed among the rude, simple people who surrounded me during my youthful days. My first piece of cloth was 56 yards long, and it weighed 25lbs., and my finishing of it was quite an event. I was allowed to go with father five miles to the house of the employer, John Lees (‘John o’ Sally’s’), whose son “folded it up and marked it, while the father proceeded to pay for the work”, the sum being, if I recollect right, about £2”. This would include spinning the weft and weaving the piece. Joseph Bently lived somewhere in the neighbourhood of High Moor at that time.

February 28th – Never in the memory of the oldest person living was weaving at a lower ebb than at the present, especially fustians, for it is an absolute fact that goods within this last fortnight have lowered in Manchester market astonishingly, so that the masters have lowered the wages at least 5s. a piece.

May 31st. – Fustian weaving everey day worse and worse. All sorts of light goods extremely brisk, and wages tolerable good. Hatting was never brisker in the memory of man. Cotton Fustian worse and worse.

Light goods extremely brisk

Here, however, comes the dividing of the streams. The old hand industry was practically dead. The new industry “light goods” made from weft spun by machinery – 40’s for instance – which was worth then 7s. 6d. a lb., was coming to life. Imports of cotton to be spun by machinery were increasing fast every year, and so were exports of goods. Phoenix like, the new trade was rising out of the ashes of the old.

Wool still rises. Comon weaving is now selling 3s. 2d. a pond.

July 31st – Everey necessary of life is extreemly dear. Cotton such as is wove into velveteens is now selling at the amazeing price of 4s. 2d. a pond. Then great must be the misirys of poor fustian weavers.

The year 1799 seems to have been a year of high prices for cotton. It will be noted that the price of this class of cotton had gone up from 2s. 10d. in January to 4s. 2d., an advance of 16d. a pound, in six months. This advance was not caused by the scarcity of the article, for we find the import of raw cotton that year to have been greater than in any previous year, the import being 43,379,278 lbs., while in the previous year, 1798, it was only 31,880,278 lbs. The kind of cotton used for fustians and velvets was chiefly what was called West Indian, or what we now call Sea Island cotton. The price of this cotton in 1799 ranged from 18d. to 55d. per lb., and of American from 17d. to 60d. per lb. Some idea may be formed of the proportionate supply of cotton from 1796 to 1800 from various sources by the following table, the figures representing bales of 400 lbs. each:-

From the United States 22,480 bales

Brazil 10,670 bales

the British West Indies 32,890 bales

the Mediterranean 16,250 bales

the East Indies 8,310 bales

Sundry other places 1,770 bales

Total in five years 93,370 bales

Ellison, from whom I have quoted all these figures, says:- A very unsatisfactory state of things existed in 1799, owing to the high prices then current. On the whole, however, the disturbed state of the Continent during the closing years of the eighteenth and the opening years of the nineteenth centuries wasdecidedly beneficial to the cotton industry in particular, and to the trade of the country in general. Internal peace and immunity from invasion admitted of uninterrupted progress in our domestic manufactures, while the victories of our admirals and the successes of our privateers threw the carrying trade of Europe almost entirely into the hands of British shipowners. In 1797 prices gained 9d. to 15d. per lb. The upward movement continued in 1798 and 1799, and in the last-named year Brazils touched 4s. 2d. to 4s. 8d., Orleans 3s. 2d. to 3s. 3d., Boweds 2s. 11d. to 3s., Sea Islands 5s. to 5s. 3d., and Surats 2s. 6d. to 2s. 9d. per lb. Once more Manchester appealed to the East India Company to stimulate the shipment of cotton from their Eastern possessions. The imports of Surats and Bengals in 1799 and 1800 averaged 16,000 bales of 400 lbs each, against only 4,400 in 1798 and 2,000 in 1797, but they could not be sold, and the company, writing to the governor of Bombay in May, 1800, trusted to his exertions for providing tonnage for our returning shipping without the aid of this article. The consequence was that the import of “this article” fell from 16,000 bales of 400 lbs. in 1800, to 1,700 bales in 1805. Our machinery at that time was evidently not adapted to spin short-stapled cotton. Poor old Rowbottom thought the world was coming an end when the price of cotton in Oldham got to 4s. 2d. per lb. The average price for the year seems to have been 3s. 4d., and the selling price of 40’s twist was only 7s. 6d., leaving a margin for capital and labour of 4s. 2d. per lb. Great indeed must have been the “miserieis of the poor fustian weavers” – at least from Rowbottom’s point of view. Did he not remember 40’s twist in 1779 at 16s. per lb., and cotton only 2s. per lb., leaving a margin of 14s. per lb., and even in later times, in 1784, was not 40’s sold at 10s. 11d. per lb., and cotton only2s., leaving a margin of 8s. 11d. per lb. These were the good old times for cotton spinners. When the margin had been so reduced well might Rowbottom write his jeremiads. With regard to the high prices of cotton and other products, it must not be overlooked that paper money had a great deal to do with them, some trading commodities being enhanced in vale 30 to 40 per cent. Rowbottom, however, only wrote of the fustian trade as carried on in the old style.

September 23rd – Extreme wet cold weather still continues, and all the neccessarys of life advancing, weaving of all sorts lowering, calicoes 6d. a cut; fustian every day is still lower and lower.

Great fall of cotton. This article of commerce, the very best for weaving velveteens, &c., is now selling at 2s. 8d. a pound, and inferior sorts between 2s. and 2s. 6d.

October 13th – The most dismal times present to our view ever remembered. The season still continues so wet and cold that the fruits of the earth are all blighted, crippled, or starved, for a great deal of flowers and grain have never ripened or come to perfection, but have withered away the same as untimely buds, wich sometimes buds at Christmas. Roses, honnisucles, and a deal of flowering srubs have perrished before they fully blowed or ripened. The air is as cold as in December. The earth is wet and soft as in a wet January. Evereything has the most terrafick and gloomey appearance, such as never was known before. There is a deal of corn – say oats – wich, for lack of sun, will never ripen this season. Tradition says that the year 1735 was a similar year, but what must become of the poor? God have mercey on us.

October 31st – This day the mob assembled according to their promise, and took al the meal and flour they could light on on the road, and sold it out – flour 2s. and meal 18d. a peck, and reserved the money for the owners.

November 1st – The mob assembled again on the new road leading to Ripponden. They came chiefly from Saddleworth, and they took possession of 8 loads of flour wich they retailed out on the road at 2s. a peck

November 30th – And cotton wool is now selling 1s. 10d. Cotton fit to be used in velveteens, nine shafts, &c., 1s. 6d. to 1s. 8d. Notwithstanding, the price of fustian pieces are monsterous lowe, so that the poor weaver has from 3s. to 5s. less wages for a velveteen than when cotton was 4s. a pond, and other sorts of fustians in proportion. All sorts of light goods are extreemly bad, and very little to be obtained by the weaver. Callicoes are wove at 3s., and some at 3s. 6d. per cut; and to fill up the measure of our distress I refer you to the price of provisions. Such is the distressedness of the times that it involves nearly all ranks of people. Most of the middling rank of people are banking, and the working class are half-starved for want of provisions, the poor little innocent children crying for bread.

This is a sad picture surely. In order that my readers may understand the position, I cannot do better than quote a memorial which at that time was got up by the hand-loom weavers. I quote it from a Manchester paper of the period. This memorial lays great blame on the masters, but it will be seen from the entry of Rowbottom that “most of the middling rank of people (employers) were banking” – that is breaking. An instance is given of velveteen weaving wages being reduced to 3s. 11¼d. per man for a week of six days, of fourteen hours per day. These mistaken men were anxious for Government interference, and addressed themselves to the task of exposing that “common fallacy of wages free and unshackled, or finding their own level”.

They could not see that they were being hustled out of the way to make room for a more competent workman, namely, “Old Ned”. It took many years to teach them this. There were men living among them who could look over their shoulders, however, and who were bold enough to resist the idea of State-protected labour. Here is the memorial:-

“To the Nobility, Gentry, and People of Great Britain”

“We , the undersigned, in conjunction with the cotton weavers of the several counties of Chester, York, Derby, and Lancaster, intend to present a petition next meeting of Parliament, praying for leave to bring in a Bill to regulate the length and breadth of pieces, the settling of wages, the pay and price of labour, &c., &c., from time to time as occasion may require, in such manner and under such rules and regulations as to the honourable Commons of Great Britain may seem meet. In carrying on the said petition frequent attempts have been made to prejudice the public mind against us by insinuating that we were connected with seditious societies.

We hereby solemnly declare that such insinuations are founded on the grossest misrepresentations, that we have no connection with political societies of any description, being, a body of labouring people subject to such impositions that we presume were never borne by any other in Britain, surrounded on every side by designing men, who daily endeavour to caluminate and misrepresent.

We are necessitated to appeal to the nobility and gentry of the country at large, humbly soliciting their serious attention to our situation, which we will endeavour to lay before them as plainly as possible.

Our grievances consist chiefly in the reduction of our wages, the lengthening our pieces without an equivalent, together with the increasing quantity of our work, arbitrary abatements of our wages, after they have promised us one sum giving us far less, some masters giving one price for work, some more, some less; all lengths are made from fifty to seventy yards at the same money, and perhaps the seventy in some places less for working than the fifty. Pieces that a few years back were made at the length of thirty-two yards have been increased to the above length. Masters striving with each other in lengthening the pieces and reducing the wages of their workmen, have brought them into the most distressing condition”

This is a sad picture surely. In order that my readers may understand the position, I cannot do better than quote a memorial which at that time was got up by the hand-loom weavers. I quote it from a Manchester paper of the period. This memorial lays great blame on the masters, but it will be seen from the entry of Rowbottom that “most of the middling rank of people (employers) were banking” – that is breaking. An instance is given of velveteen weaving wages being reduced to 3s. 11¼d. per man for a week of six days, of fourteen hours per day. These mistaken men were anxious for Government interference, and addressed themselves to the task of exposing that “common fallacy of wages free and unshackled, or finding their own level”. They could not see that they were being hustled out of the way to make room for a more competent workman, namely, “Old Ned”. It took many years to teach them this. There were men living among them who could look over their shoulders, however, and who were bold enough to resist the idea of State-protected labour. Here is the memorial:-

“To the Nobility, Gentry, and People of Great Britain”

“We, the undersigned, in conjunction with the cotton weavers of the several counties of Chester, York, Derby, and Lancaster, intend to present a petition next meeting of Parliament, praying for leave to bring in a Bill to regulate the length and breadth of pieces, the settling of wages, the pay and price of labour, &c., &c., from time to time as occasion may require, in such manner and under such rules and regulations as to the honourable Commons of Great Britain may seem meet. In carrying on the said petition frequent attempts have been made to prejudice the public mind against us by insinuating that we were connected with seditious societies.

We hereby solemnly declare that such insinuations are founded on the grossest misrepresentations, that we have no connection with political societies of any description, being, a body of labouring people subject to such impositions that we presume were never borne by any other in Britain, surrounded on every side by designing men, who daily endeavour to caluminate and misrepresent.

We are necessitated to appeal to the nobility and gentry of the country at large, humbly soliciting their serious attention to our situation, which we will endeavour to lay before them as plainly as possible.

Our grievances consist chiefly in the reduction of our wages, the lengthening our pieces without an equivalent, together with the increasing quantity of our work, arbitrary abatements of our wages, after they have promised us one sum giving us far less, some masters giving one price for work, some more, some less; all lengths are made from fifty to seventy yards at the same money, and perhaps the seventy in some places less for working than the fifty. Pieces that a few years back were made at the length of thirty-two yards have been increased to the above length. Masters striving with each other in lengthening the pieces and reducing the wages of their workmen, have brought them into the most distressing condition”.

|

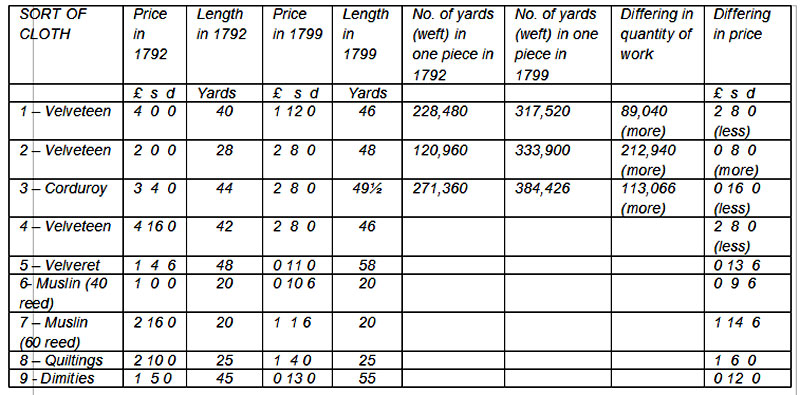

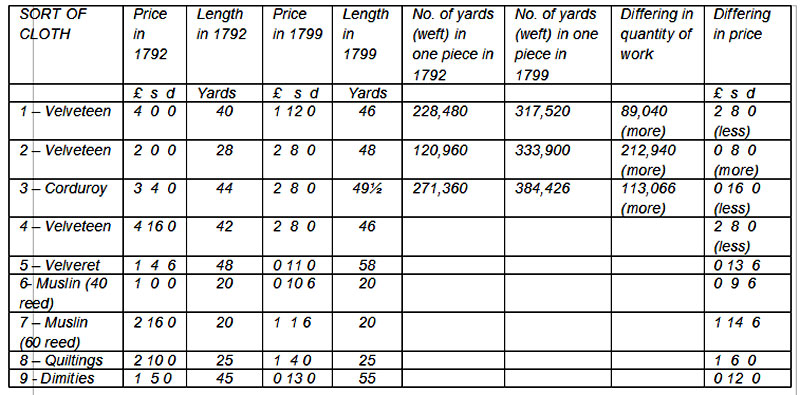

N. B. – The first four sorts are manufactured out of the raw cotton for prices affixed to them. It is to be observed that every sort is reduced in a similar manner to the above. A variety of practices prevail in the manufactory that ultimately tend to injure it and the workmen, such as making thin and shallow goods, as for instance thick middles and thin ends in muslins, thin ginghams, and muslinets, well callendered quiltings made light, velverets, thicksets, &c., made up in so slight a manner that they do not answer the expectations of the purchasers, thereby bringing the manufacturers into discredit. Added to this the constant impositions practised on those employed in working the goods, together with a variety of other injurious practices, all tending to expose that “common fallacy of wages free and unshackled or finding their own level”. Upon these pretences the wages of the workmen have been reduced in the manner above mentioned, and we will show by an accurate calculation what it is possible for a workman to get per week by constant hard labour, together with what he might have got in 1792 at the same rate of working, and show the reduction of his wages per week.

1st. What a person may get by working velveteen. Admitting a person extremely diligent to work one piece in 12 days of 14 hours per day each, that is 26,460 yards of weft per day without intermission. Admitting a second to prepare the cotton ready for carding, to rove and spin it in the same time, it will be 26,460 yards, multiplied by 312 days will be 8,255,520 yards of weft in one year, which divided by 317,520 yards, the number in one piece in 1799, the quotient will be twenty pieces at £1. 12s., making £41. 12s. for two persons. Now, the next thing to be considered is how much of the above sum is not money. In the first place, to enable two persons to

work 14 hours per day they will be necessitated to use 46 lbs. of candles in the year:-

Candles, 46 lbs., at 9d. per lb. £1 14 6

Carding 468 lbs. at 2d. per lb 3 18 0

Bobbin winding, 468 lbs at 2d. 3 18 0

Flour for dressing, iron heating,

Shop room, repair to utensils, &c. 2 12 0

________

£12 2 6

Which, deduct from £41.12s. leaves £29. 9s. 6d., divided betwixt two person will be each 5s.8d. per week. The next to be shown is what the same rate of working would have been in 1792: 26,460 yards, multiplied by 312 days, will be 8,255,520 yards as before. Now, on examining the above table, it will be found that in the year 1792 one piece contained 228,480 yards of weft; divide 8,255,520 yards by 228,480 will give 36,132 pieces, at that time £4 per piece. 36, 132 pieces at £4 would amount to £144 10s. 6½ d; subtract as before £12. 2s. 6d., the remainder, £132. 8s. 0½d., divided betwixt two persons, will be £1 5s. 5½d. per week each person. Subtract 5s. 8d., and it will prove a reduction of 19s. 9½d. per week in the wages of one person.

Here follows a calculation of what a person might earn by working six yards per day of velveret for 312 days of fourteen hours each day: 312 days, 6 yards per day; total 1,872 yards. 60 – 31 pieces 12 yards at 11s. per piece will be about £17 1s. Subtract £6 13s. 9d. for bobbin winding, candles, &c., &c., will leave £10 7s. 3d. Divided by 52 weeks, will be 3s. 11¼d., so that a person must constantly work six yards per day to earn 3s. 11¼d. per week. What he might have got at the same rate of working in the year 1791: - 312 days, six yards per day; total 1,872 yards. 48 yards, 39 pieces, at £1 4s. 6d., £47 15s. 6d. Subtract £6 13s. 9d., will leave £41 1s. 9d. Divided by 52 weeks, will be 15s. 9½d. per week, which proves a reduction of 11s. 9¼d. per week. Dimities, muslinets, and ginghams are little better than the above. Muslins and some sorts rather better, but those that are something better are going fast after the heels of the others. A reduction in most sorts is now taking place. Ginghams, three months ago 4½d. per yard, are now worked at 2d. Muslins reduced 2s. to 3s. per piece, and that little that remains of our wages is far from being secure to us, unless the legislature in the plenitude of its wisdom, will grant us such regulations as will in future protect us from the impositions we at present labour under. We shall offer no comment on our situation, believing it will be plainly understood by all who come to a knowledge of the above facts. We earnestly solicit the support of those whom we address on behalf of ourselves and fifty thousand of our fellow-weavers in the utmost distress, and are with the greatest respect their humble and obedient servants,

Richard Owen, James Draper, Thomas Haslam, John Roper, George Beswick, Thomas Knowles, Ralph Hart, Joseph Shufflebottom, Thomas Thorpe, John Settle, William Riding, James Holcroft, John Greenhalgh, William Haslam.

Bolton, Lancashire, Dec. 16th, 1799 |

|

|