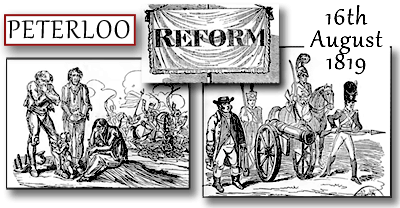

The Peterloo Massacre - Manchester 16th August 1819

Rowbottom's Comments on Trade and Politics - 1800 to 1819 1810 The year of 1810 commenced on a Monday, wich was a dark cloudy day, and Cristmas was better kept up than last year, although but a miserable Cristmas compared with former times, but trade is better than last winter a great deal; Hatting was never better at this time of year. Factory business is brisk, and wages moderate, but everything is so immencely dear that the poor cannot make a Cristmas at all, and better days never need be expected as long as there is continuation of this lamentable war. The growth of our local industries is clearly marked in this annal. “Hatting was never better at this time of year;” “Factory business brisk,” &c. The times favoured those who had capital on account of the inflated value of money. The poor were badly off enough on the account of the dearness of provisions. E. Butterworth says of this period: “The facility with which credit could be obtained at this period, multiplied artificial capital, and imported prosperity in trade during the war. As well as adversity coincident with its advance. January 3rd - The earnings of the hand weavers would be little more than one penny per hour. The day’s work often lasted well into the dark hours in winter, a day of 15 hours’ duration being common enough in our old loom houses; 13s. to 20s. was a good price though we have seen Tabbys done for 12s. to 14s. in these annals. Hatting owing to stuff being so bad the work is very tedious to perform. Out work is torable plenty. All sorts of timber dear; pitchpine, deal, is selling 6s. a foot. Weavers’ brushes, which 30 years ago sold 1s. per pair, now sell 3s. 1. These weavers brushes were used for “deeting” the “yorn” in the loom and had to be furnished at the weavers’ expense, as also were the “sow” and the drying irons. What a tedious thing it must have been to size the warps in the loom! I suppose there must have been a great scarcity of bristles made the brushes be so dear. February 10th - August 1st – The country seems to have been almost drained of cash, and paper money had taken its place. William Cobbett was at this time a prisoner in Newgate, and spent his time in writing his famous letters on “Paper v. Gold.” These letters were addressed to the “people of Salisbury, because those people were suffering severely from the failures of country banks.” He therein traces the history of paper money from the outset to the day wen the people of Salisbury became all in a moment destitute of the means of getting a dinner. Not only were the people of Salisbury put to trouble, but Oldham people suffered severely. Country banks had sprung up like mushrooms. In a very few years they had increased throughout the country from 230 to 721 in number. Banking was a profitable business when money could be made out of paper, and the issue was almost unlimited. The “guineas” were nearly all bought up and sent abroad, and “people in trade purchased at a premium with bank notes the things called shillings and six-pences from the keepers of turnpike gates.” The Bank of England had not recovered its position since its suspension of payment in l797. It had no branches outside London. The trade of the country was, therefore, in the hands of the country bankers, who it appears were a sorry lot. Many of them failed during this crisis. Cobbett estimates that country bank notes were afloat in 1809 representing £70,000,000 of money, and implies that it would be stupid to believe that country bankers have, or ever will have, gold or silver sufficient to pay off a thousandth part of the notes that they have issued. I know not what local banks we had in Oldham at that time, but I know that an uncle of mine would not trust any bank, and lent his money to old John Travis, who seems to have stood in the place of banker to many of our earlier cotton spinners. I need hardly remark that an amount expressed in bank notes by no means corresponds in value with the same amount expressed in gold and silver. Moreover the danger of forged bank notes was serious and ever present. August 8th – The state of the currency was such as to place the trade of the country in a perilous position. No one knew what he was really worth, nor indeed whether he was worth anything. The bills and bank notes in the hands of country manufacturers in many cases not being worth the paper they were inscribed on. August 25th - September 19th – The weavers could not tell whom to blame for the bad state of their trade. The number of power-looms kept increasing, and they thought this was the cause of their distress, and, as we shall see, they eventually wreaked their vengeance on the power-looms by smashing them up and burning the houses of those who owned them. |

Return to Commodities & Trade Page