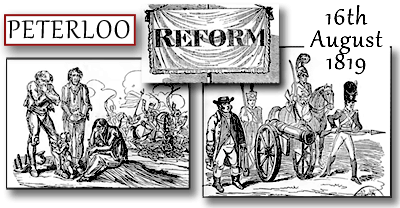

The Peterloo Massacre - Manchester 16th August 1819

Rowbottom's Comments on Trade and Politics - 1800 to 1819 1816 The year one thousand eight hundred and sixteen commenced on Monday, wich was a remarkable fine day, and in consequence of the reasonableness of some kinds of provisions poor people had a merry Cristmas, and where amply supplied with roast beff, ale, and pies, and it may with truth be said that poor people have not had such a happy Cristmas for a series of years, for there is universal peace with all the world which causes plenty. Prentice says of this year the industrial classes “had thought that with peace there would be plenty.” They were bitterly disappointed however. The following is an authentic statement of the price of the following articles:- Meal, 1s. 9d. to 1s 10d.; flour, 2s. 2d. to 2s. 4d.; malt, 2s. 5d. to 2s. 6d.; treacle, 4d. to 4 1/2d.; butter, 11d. to 13d.; new butter, 16d.; candles, 7 1/2d. to 81/2d.; pork, 4 1/2d. to 6d.; beff, 6d. to 7d.; mutton, 6 1/2d. to 7d.; bacon, 7d. to 8d.; hops, 2s. 6d.; salt, 4d.; onions 1 1/2d.; sugar, 10d. to 13d.; soap (white), 9d. to 11d.; brown soap, 8d. to 10d. a pound; pottatoes, from 7 1/2d. to 9d. a score; peas, 4d. a quart; green peas, 5d. a quart; hay, 9d. to 9 1/2d. a stone; straw, 5d. a stone; white cotton comonly cald boads, 15d. to 15 1/2d.; bale cotton, 17d. per pond; coals, from 20d. to 2s. for two baskets or a horse load at the pit. [data HERE] This list of prices is interesting, as it shows a considerable fall in the prices of some domestic articles since the beginning of the previous year. When we consider that the Corn Bill had been passed some eight months before, this decline may not have been expected, but one must remember that a settled peace had no doubt a great influence in bringing down prices temporarily at least. The price of cotton had been greatly reduced. James A. Mann says: “In 1816 the growth of cotton received a permanent stimulus: the demand, which, under a state of war of twenty years’ duration, had continued oppressed, assisted by the opening up of the foreign trade of the country and the close of the war in 1815, exhibited a great tendency to increase, which became firmly established, and as a result, in the year 1817 we received a greatly increased supply.” The annal about the price of coal is interesting. Coals in this neighbourhood were originally sold by measure, not by weight. A basket weighed about 2 cwt.; two baskets, therefore, weighed about 4 cwt. Now a donkey load in a sack thrown over the donkey’s back was a basket, or 2 cwt., and it seems a horse load in the same way – namely, in a sack on the horse’s back – was two baskets, or 4 cwts. When it speaks here of a horse load, it does not mean a cart load, but a load put on the horse’s back. Trade in general brisk; wages moderate; hatting very scarse; every appearance of provisions being still lower. This remark probably alludes to the cotton trade, which, during this year, as already noted, received a great impetus, though its effect was chiefly felt in the following two years. February 17th These poor hatters seem always to have been living on the edge of their cake. Trade could not have been long bad since the last revival, and yet we now read of them as being in a state of starvation. It shows how different must have been the condition of the people then to what it is now. People in these days can withstand a siege almost without starving. Then it seems as if they had but very little beforehand even taking into account their credit with the shopkeepers... Cotton spinners must have been doing well as regards supply and demand, “twist for exportation” being a special feature in the trade. Our system of finance, however, was sadly defective. Country banks were stopping – Old Cobbett’s prophesies were coming true. Paper money was the chief means of exchange, and the strongest bank in England was not safe. Trade, by the emence number of failures is very flat, especially the different weaving branches and hatting. The factory business was never better. The orders for weft for twist and exportation are numerous. There would appear to have been almost three winters for one summer these two years, as we shall see there was hardly any summer at all in 1816. “Factory business never better.” This annal quite agrees with the official returns for that year. Weft and twist for export evidently found a good market. I quote the official value returned to government for 1816 and for two previous and two succeeding years, of yarns and twist exported from the United Kingdom, showing an increased value in 1816.:- 1814, £1,119,850; 1815, £808,853; 1816, £1,380,486; 1817, £11.125.258; 1818, £1,296,776. A deal of merchants are becoming bankrupts wich trows the greatest stagnation on trade, and all sorts of weaving growing dayley worse and worse. A deal of country banks have failed, and more are expected to follow the same example, which trows the greatest distress on the comerce of the country [following the April rise in price of Flour] This rise in the price of flour, it must be remembered, was in the beginning part of the year, April. It would most seem as if there was a conspiracy to force up the price of flour. Speculators were evidently at work on the prospect of a bad harvest. This is clear from the fluctuating prices here quoted. The “corn bill” had placed the poor at the mercy of the rich. Lamentable and distressed situation of the poor weavers is behind all comprehention. Velveteens, cords, &c. are wove at from 18d. to 20d. per pond, and all other sorts of fustian goods in proportion. Light goods are still worse if posable; a deal of kinds are wove at one-third than they were two years ago, and to meet all this flour is taking a rapid rise. May 1st - Weaving is every day worse. The general wages now paid is from 16d. to 18d. a pond, 24 hanks;some indeed for exalent work will get up to 19d. a pond. Tabbys must be very good ones wich are 20s a c…… Light goods are worse if posable than strong fustians, and a deal of weavers out of employ. June 17th - The steam loom is evidently here making itself felt, judging by the prices of weaving. Cotton spinners were evidently suffering from fiscal rather than from other causes. The reduction of 1/4d. a score for spinning had been previously attempted, and caused a six weeks strike in 1815. August 23rd - ... The great reduction in weaving prices was evidently the result of introducing steam looms, though M. Kennedy only estimates the number of power looms at 14,000 to 15,000 in 1819. While the number of hand-looms was 240,000. It is painfully interesting to see the fall in the prices for weaving... A Public meeting was held at the Angel Inn, Oldham, to take into consideration the distressed state of the poor. October 31st The Angel Inn at that time was certainly not the hot-bed of Radicalism. It was at the Angel where only the year before the leaders of the town had met to express their sympathy with and to extend their help to those who had fought and bled at Waterloo. All honour to that movement. As to the nature of the distress, I need but refer my readers to the newspapers of the time. Everybody was suffering; and what made the suffering more intense was the disappointed hopes of the people who fondly dreamt, and even sand of “Lovely peace with plenty crowned.” According to Butterworth, the meeting mentioned in this annal entered into subscriptions for the relief of the poor affected by the distress. No doubt, the growing town of Oldham, with its factories absorbing its surplus labour, would suffer less than most other towns; but even here the people were suffering from the change of an old established industry on to new lines, in addition to other common troubles, and the misery of the poor must have been beyond the conception of those who live in these halcyon days. On the 8th of October, 1814, the Earl of Darlington wrote to Lord Sidmouth, the home Secretary:- “The distress in Yorkshire is unprecedented. Wheat is already more than a guinea a bushel, and no old corn in store. The potato crop has failed. The harvest is only beginning (Oct. 8, mind), the corn being in many parts still green, and I fear a total defalcation of all grain this season from the deluge of rain which has fallen for several weeks, and which is still falling.” |

Return to Commodities & Trade Page