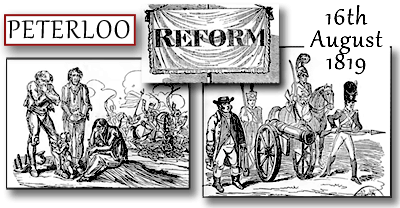

The Peterloo Massacre - Manchester 16th August 1819

Rowbottom's Comments on Trade and Politics - 1800 to 1819 1817 Rowbottom’s annals for 1817 are missing; their place must therefore be supplied from other sources. John Higson and E. Butterworth have both preserved scattered notices of the events of this year. E. Butterworth says:- On the 3rd January, 1817, an unusually numerous Radical Reform meeting was again held on Bent Green (known now as Bent Grange), when a banner bearing Radical mottoes and a band of music imparted peculiar animation to the events of the day. This was the second Reform meeting held at Oldham. Oldham Radicals were evidently fully alive to the interests of their cause, and they seem to have been persistent in their demand for reform, nor were they alone. Reform meetings were held in most of the neighbouring towns, and Manchester seems to have been the centre of the reform movement. On the 13th of this month a meeting of the inhabitants of Manchester and Salford was held to consider the necessity of adopting additional measures for the maintenance of the public peace. The more peaceable inhabitants were evidently greatly alarmed at the aspect of public events. We are told the organised system of committees, delegates, and missionaries, contributions levied, pamphlets disseminated, language of intimidation used, and the appointment of popular assemblies in various parts of the kingdom on one and the same day afforded strong manifestation of mediated disorder and tumult, and bore no analogy to the fair and legitimate exercise of that constitutional liberty which is the birthright and security of Englishmen. See Wheeler, p.108. There can be no doubt that both sides suffered from being over-zealous, and it was this which hindered the progress of real reform. Some of the leaders of Reform in Oldham and elsewhere were men of sense, who afterwards were greatly esteemed, but some of the followers were no doubt of dangerous character, and their fervency in the cause was such as to cause distrust and dismay even to their own party. On the part of the Government much mischief was caused by not properly gauging the real evils from which the country suffered, evils which it cannot be denied had their rise in misgovernment. During the year 1816 a Hampden club was formed in Middleton, which seems to have been a kind of Radical centre, as we find that delegates from other localities – among whom were some leading reformers – sometimes met there. The meeting place was an old disused chapel, once held by the Kilhamites. Sam Bamford tells us the following Radicals occasionally attended the meetings of the club:- John Knight, of Manchester, Cotton manufacturer in a small way, formerly of Mossley, who was a very earnest champion of the cause; William Ogden of Manchester, whom Canning once referred to as the “revered and ruptured Ogden;” William Benow, of Manchester, shoemaker, Charles Walker, of Ashton, weaver, Joseph Watson, of Mossley, clogger, Joseph Ramsden, of Mossley, woollen weaver, William Nicholson, of Lees, letter-press printer, John Haigh, of Lord’s Gate, Oldham, silk weaver, Joseph Taylor, of Oldham, hatter, John Kay, of Royton, cotton-manufacturer, William Fitton, of Royton, student-in-surgery, Robert Pilkington, of Bury, cotton weaver, Amos Ogden, of Middleton, silk weaver, Caleb Johnson, of Middleton, cotton weaver, and S. Bamford, of Middleton, silk weaver, whose book, entitled “Passages in the Life of a Radical,” ought to be re-printed in a cheap form , and read as a class-book by politicians of all shades of opinion. As showing the opinions held by these early reformers, Bamford says,:-

February 10th - E. Butterworth says a third Radical reform meting was held on Bent Green. The authorities became alarmed, and a number of special constables were appointed on the 8th. In addition to the civil power, a body of soldiery of the 54th Regiment of Foot, 104 in number, were stationed in a temporary barracks in Fog-lane, which they first occupied on the 3rd March 1817 What was called the “Green Bag Inquiry” was instituted about this time, so named from a green bag full of papers supposed to have been of treasonable character having been laid before Parliament by the Prince Regent. Secret committees were appointed by Parliament, the result being the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, on the 3rd March. The Government adopted a system of espionage, which created much of the mischief which it was supposed to discover. These spies were distributed through the country. Bamford mentions one of the name of Oliver, who was busy in the summer of 1817, who tried to lead the reformers into mischief, and then would have “split” upon them. March 10th - (says E. Butterworth)

|

Return to Commodities & Trade Page