The Peterloo Massacre -

Manchester 16th Aug. 1819 |

||

Almost 200 years ago, [writing this in April 2018], 60 thousand working men, women and children, came together for a mass rally in Manchester in order to hear what the radical reformer, Henry 'Orator' Hunt had to say, and to show their support for social and political reform. Their wishes were for a fair days' pay for a fair day's work; for decent food on the table and a roof over their heads. To achieve this, they needed to have their collective voice heard, through their own MPs who would represent the evolving industrial towns and cities. The first step would need to be the Reform of Parliament.

Looking back, we know that those plans went terrribly wrong as the enthusiastic and hopeful atmosphere turned into one of terror as the thronged field was broken up by the charging Manchester Yeomanry Cavalry, brandishing newly sharpened sabres and leaving almost 20 dead, and over 600 wounded ... a substantial number of whom were maimed for life - shorter rather than longer in many instances. To understand the significance of Peterloo we need to put it into its historical context. Historically, British lower classes had been largely patriotic - loyally supporting 'king and country' and the established order; they knew 'their place' in the ordained hierarchy - they were the 'lowers orders' - and there they must stay. However, the previous 50 years had seen the American War of Independence and the resultant loss, to Britain, of the colonies; this was closely followed by the French Revolution which saw the Royal Family guillotined, along with those of the aristocracy who didn't flee; then there was the Reign of Terror when no-one was safe from the guillotine. Coming even closer to home, and many in Ireland were demanding 'self rule' ... making the British Government ever more nervous and fearful of revolution on their own doorstep. As the country approached the new century the catalysts for radical change were coming into play. They included : Instead of addressing the causes of unrest, the Government sought to control the situation by repressive measures to crush the working class spirit and to protect the wealthy and landed gentry. It was against this background, as the years passed, that: The working man was left defenceless ... hungry ... and desperate. By 1819, great hardship was being endured, in many areas, bringing disatisfaction, misery, resentment and deep anger at the perceived injustice of the working man's situation, under the increasing burden of taxation to fund the Prince Regent's personal extravagance and the enormous costs of the wars with France. By this time, Henry (orator) Hunt, had emerged as a strong and insistent voice for reform. Amongst other things, he called for a repeal of the Corn Laws, universal manhood suffrage, secret ballots and an annual parliament. Hunt's policy to bring about reform was one of strong and continuous constitutional pressure on government ... revolution was not a part of it. One of Hunt's early admirers, was a local weaver called Samuel Bamford - a radical, with a strong social conscience and aspirations to become a published poet. Through his own autobiographical works, 'Early Days' and 'Passages in the Life of a Radical', we know a good deal about what was happening at that time. Samuel had been born in Middleton in 1788 and, after a number of different jobs, he returned to his roots and became a weaver in Middleton. In 1816, the already politically aware Samuel became secretary of the Middleton Hampden Club which functioned as a society for debating political issues and campaigning for reform. Other local branches were formed - in Royton (which had been the 1st outside London), Oldham, Rochdale, Manchester and Ashton under Lyne. For a penny a week they would meet and read the latest radical publications and newspapers such as the 'Manchester Observer', 'Black Dwarf', 'Sherwin's Political Register' (which later became 'The Republican') and Cobbett's 'Political Register' ... and then debate the issues raised. In January 1817, Samuel was a delegate to a London convention of the Hampden clubs, the purpose of which was to discuss a proposed Reform Bill, to be presented to the House of Commons. The years of localised riots and unrest had convinced the Home Secretary, Viscount Sidmouth, that Revolution to overthrow the government and monarchy was being plotted and, was further convinced, that it was in the Hampden Clubs that this plotting took place.

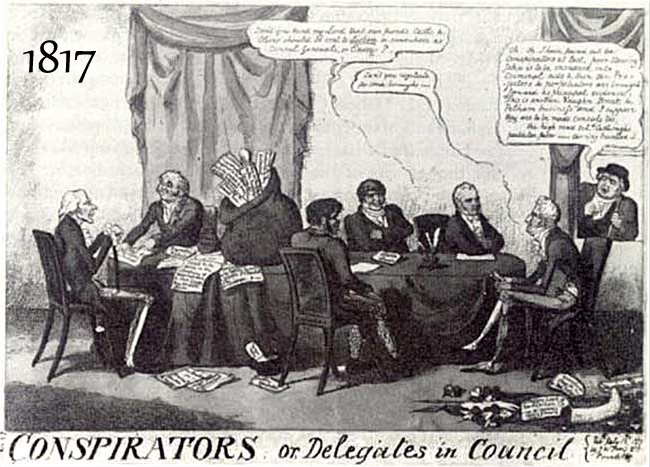

This cartoon, dating from 1817, illustrates the nervous reaction of the government as they operated their 'spy system'. Spies were not only employed to report on anything suspicious that they could find but were also encouraged to create 'honey-traps', by instigating revolutionary plots, in order to ensnare the unwary, thereby providing the spy-masters with excuses to crack down on the leaders. One such plot appears to have been that of the Blanketeers' proposed march to London, in 1817. Manchester's Deputy Chief Constable, Joseph Nadin, notoriously implicated in the later Peterloo Massacre, rounded up and arrested the supposed local organisers, including Samuel Bamford. Samuel had spoken out against the idea of the march, sensing a trap but, even so, along with the others, he was arrested and sent to London in irons. They were held there for several months - before being released without charge. On their release from prison they formed the 'Patriotic Union Society', and it was this body which organised the ill-fated Meeting, in August 1819, on St Peter's Field in Manchester. The object of the meeting was to promote the need for representation in parliament and the notice in the Manchester Observer read, "The public are most respectfuly informed, a meeting will be held to take into consideration the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical Reform in the Commons House of Parliament, being fully convinced that nothing less can remove the intolerable evils under which the People of this country have so long, and do still, groan ... " and went on, " ... to consider the propriety of the unrepresented inhabitants of Manchester ... electing a person to represent them in Parliament ..." Originally planned for the 9th, the meeting had been refused permission to go ahead but, on appeal, and with the emphasis on new wording, and no rejection from the magistrates, the planners believed that permission was implicit. Behind the scenes, it appears that the Manchester Magistrates had possibly resolved to use this opporunity to send a signal to radical reformers that their message was unwelcome and would be strongly opposed. Just how much of what happened on the day was orchestrated, is still open to debate. 200 years of lies and cover-up is difficult to penetrate to find the truth! Letters between the Magistrates and Lord Sidmouth appear to suggest that the Magistrates could infer that any use of force to disupt the meeting would have the approval of Westminster as long as it wasn't overtly illegal. Still politically very active but careful not to fall into another trap or fall foul of the law, again, Samuel was determined that the mass Reform meeting, planned for August, would reflect credit on the marchers. He intended that they would prove that the working man could rise to the challenge of responsibility and behave in a moderate manner that would convince the doubters of the justice of their claims. To this end, he determined that the Middleton contingent would march in an orderly fashion, well-turned out, sober and restrained. Prior to the Big Day, groups of men would meet after work to practise military-style drilling so that instructions could be carried out cleanly and without the march becoming shambolic. No sticks or weapons were to be tolerated. In the early morning of the 16th August, the reformers, of the villages and towns around Middleton, met up in their Sunday best outfits, along with their wives and children, for what was to be a day out ... but one with a serious purpose. It was a beautiful, warm summer's day. The Oldham Contingent met up at 9am on the Village Green, Bent Grange and were joined there by the Chadderton contingent. Later, along the route, they were joined by the Failsworth Radicals. According to one account, there were 16 banners and 5 caps of Liberty in this local group. The Oldham Banner was described as " most beautiful ... of white silk." The Royton section carried 2 banners of red and green silk, one of which belonged to 'The Royton Female Union', with 200 women, dressed in white, marching alongside it. There are several first hand, witness accounts of the events of that fateful day as they unfolded.On the main points, they generally tally. The discrepancies that occur depend on where the witnesses' sympathies lay. Eye witness reports state that, although the numbers of people were enormous and the marchers were in formation, filling the streets, the general atmosphere was one full of good humour; of general chatter and laughter; bands were playing and flags waving. Notwithstanding, men had been employed by the magistrates, to clear the field of any rocks, or broken bricks etc., that could be used as missiles in the event of a riot. As the marchers set off from their different villages, the Manchester Magistrates met for breakfast, at Star Inn on Deansgate, to consider their options for the day ahead. Amongst this Government appointed number, there would be no sympathy for the cause of the approaching marchers. Early morning ... and on the the south side of the empty field, near Windmill Street, the hustings platform was being erected, ready for the speakers who would include Henry Hunt and Oldham's John Knight. As the hour of the meeting drew nearer the marchers entered Manchester from all directions, marching through the streets and converging on St. Peter's Field; gathering near the platform or on the raised ground at the end of Windmill street near the corner of Mount Street. On Mount Street, the Magistrates moved into one of the houses overlooking the field, to observe the proceedings. In the adjoining houses, other people were watching from their own windows. 200 special constables were already lined up forming an avenue from Mount Street, through the crowd, to create access to the hustings, and allow arrests when necessary. Henry Hunt, along with the other speakers, Johnson, Knight and Moorhouse,and with Mrs. Mary Fildes, arrived in a barouche and entered the field by the corner of Peter Street and Watson St. The carriage made its way, with diffculty, through the crowd to the hustings. There, they joined several newspaper reporters, amongst whom was : John Tyas for the 'London Times', Edward Baines for the 'Leeds Mercury', John Saxton of the 'Manchester Observer', and John Smith for the 'Liverpool Mercury'. The radical publisher, Richard Carlile, was also present. Henry Hunt opened proceedings and started his speech. It's at this point that accounts begin to differ wildly as later versions sought to justify the actions of those in authority. The magistrates at the window now either panicked or proceeded with an already decided-upon plan of action. 30 townsfolk, including Richard Owen and Mr. Phillips, signed an affidavit to the effect that they "considered the town was endangered" thereby justifying the arrest of the speakers. A warrant was accordingly drawn up for the arrest of the 4 speakers. Joseph Nadin, the Deputy Constable, was instructed to carry it out. Significantly, Nadin requested - as a vital necessity - the assistance of the Military in carrying out these instructions. Riders were instantly despatched to bring in the troops who were already positioned, out of sight, in the nearby streets.

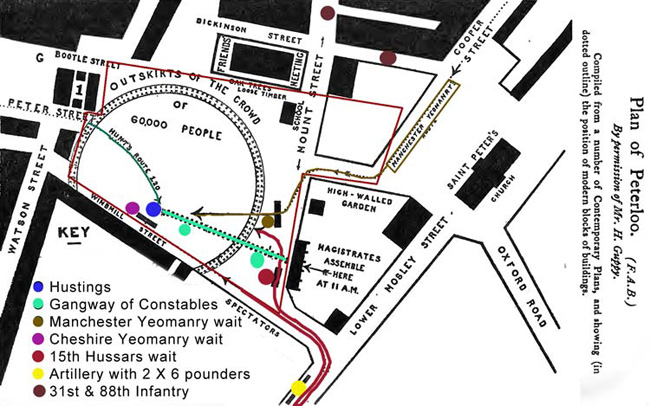

This map (from 1919) helps to show the troop movements and set the scene for what happened. The blue circle is the hustings and the line from Peter Street to the hustings is the route of Henry Hunt's carriage. The avenue of 200 special constables is shown leading from the house on Mount Street to the hustings. The Manchester Yeomanry, who had assembled on Cooper Street, were the first to arrive on the scene. They had set off at a fast pace along Cooper Street and, along the way, one of the troops catching up at a gallop, knocked down a woman with a young child. That 2 year old child, called William Fildes, was killed and became the first fatality of Peterloo. The Manchester yeomanry, with their newly sharpened swords, arrived from the NE corner of the field and turned left along the houses on Mount Street, where they paused for a few minutes, in what was described as 'great disorder', before almost immediately charging into the crowd and towards the hustings. The 15th Hussars had assembled, with their artillery, on Lower Mosley street, near the corner of Windmill Street. On being sent for, they moved onto the field in front of the Magistrates House and waited until ordered to disperse the crowd. The Cheshire yeomanry had been positioned on Windmill Street, near the hustings, but it's unclear from reports as to when they actually entered the fray - if they even did. The Infantry don't appear to have arrived on the field until it was virtually over. Modern, animated graphics showing the events, sometimes give the impression of relatively small numbers of the military but, in actual fact, the number ran into many hundreds. Hunt was aware of the arrival of the yeomanry and shouted, "Stand firm my friends! You see they are in disorder already! This is a trick! Give them three cheers!" The Magistrates would later emphatically declare that, at this point, there was no intention to disperse the crowd with cavalry, only to arrest the speakers and, hopefully, allow the crowd to disperse quietly, as a result. In reality, and without any warning, Nadin, with the Manchester yeomanry, charged from the right through the crowd towards the hustings and the constables.

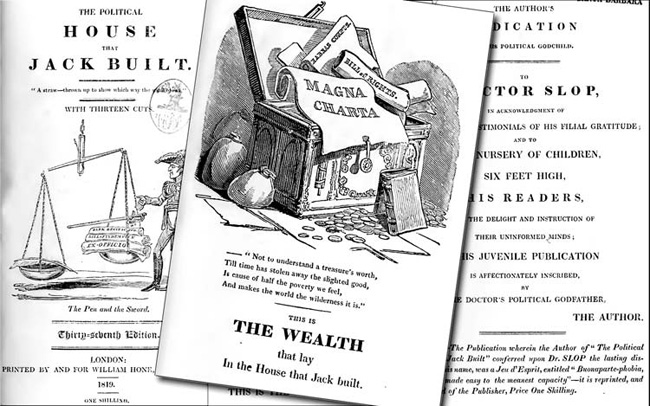

On their reaching the platform, Hunt would not surrender himself to military arrest and Nadin, as a civil police officer, made the arrests as Hunt and his party were dragged along the avenue of constables to the Magistrates' house. It is at this juncture that evidence becomes even more skewed in order to reflect the preferred version of 'truth'! Two points at cross purposes were : One troop of the Manchester Yeomanry, about 50 or 60 men, were by now surrounded by the crowd and a watching Magistrate, Mr. Hulton, decided that he could see "sticks flourished" and "brickbats thrown at the Yeomanry" - a statement which was refuted emphatically by other, more impartial, witnesses. On Hulton's order, the 15th Hussars charged into the crowd, after he exclaimed to their commanding officer, "Good God, sir! don't you see they're attacking the yeomanry? Disperse the Meeting!" Although it was maintained that the Riot Act was read from a window, of the house on Mount Street, no-one who was considered to be impartial heard it being read (not even Reverend Stanley in the room directly above). The crowd was dispersed in just 10 minutes, leaving the dead and dying amongst the scattered debris left by the terrified throng struggling to escape a field from which every means of exit was blocked by the military. Piling insult upon injury, the Manchester Magistrates received a letter from Lord Sidmouth passing on the Prince Regent's thanks for their, "... prompt, decisive and efficient measures for the preservation of the public tranquillity ..." An impassioned response was written and published by Richard Carlile in the 'Republican'. He was one of those on the hustings with Henry Hunt but, evading arrest, he escaped to write his own account, in an open letter to Lord Sidmouth, published in the 'Observer' on the 22nd of August. He was subsequently arrested and sentenced to imprisonment. He continued to edit the 'Republican' (previously 'Sherwin's Political Register') from his prison cell! Also on the hustings, on that fateful day, was a newspaper reporter from the 'Times' in London, John Tyas. He was dragged off under arrest with the others and, when released, headed back for London where he also penned an angry account of the day. Less than a week after the Peterloo Massacre occurred, it was being reported from London to Manchester and beyond. Much of the population would know of, and be horrified by, the accounts of that day. Radical presses worked overtime. If you couldn't afford a copy of the latest 'squib' or pamphlet yourself, you would find it pasted in town and city windows for all to read! The authorities probably thought that any resultant blame, or unpleasantness, could be covered up and swiftly forgotten ... how mistaken! Two centuries later and we still remember, argue about the detail, measure the sacrifice, and apportion the blame. In the months and earlier years after the event, casualty numbers could only be guesses based on the various versions of what happened. However, over the intervening years there has been detailed analysis of the surviving reports and documents relating to the aftermath of Peterloo. As a result, we can now be much more confident of the numbers hurt on the day and of the injuries they suffered, many of which were severe and life-changing. Referencing the book, 'Peterloo Casualties', by Michael Bush, it appears that 654 casulaties were identified and 18 known deaths. Many of those injured could neither find medical care nor apply for Poor Relief, when they couldn't work, as the fear of arrest and imprisonment, on account of being at the Meeting, was so great. Injuries identified were those of sabre, truncheon, bayonet or butt, trampled by horse, crushed by crowd, combinations of more than one cause, and 'miscellaneous'. A Relief Fund was set up and, by February 1820, had raised £3,408, However, when the figures are looked at we can see that much of the money was paid towards the legal fees and expenses of those arrested, with relatively paltry sums being paid to those incapacitated and unable to work. The Oldham area was one of those suffering the greatest number of casualties, 90, with several deaths, including : John Ashton, from Nr. Oldham, Thomas Buckley from Chadderton, Edmund Dawson from Saddleworth, William Dawson from Saddleworth, and John Rhodes from Nr. Oldham ... all of whom died on the Field or within the following few days. Then, during the night 6th/7th September, a hitherto unremarked Oldham man, a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo, died as a result of injuries sustained at the Meeting. His name was John Lees and, when the inquest into the cause of his death opened, reports would remain in the newspapers for weeks. The full transcript "an Authentic Account of the Inquest " ran to over 600 pages and was printed by William Hone in 1820. Long recognised as the farce it became - and over a week after his death - the inquest on John Lees opened, at the 'Sign of the Duke of York', in Oldham, on the 8th September. It seems apparent that the authorities assumed that this would be an open & shut case. He was a 22 year old mill worker, unlikely to have 'friends in high places' to make demands about 'culpability' and 'legality'. The Coroner, Mr. Farrand, was away from town so his clerk, Mr. Battye, attended in his place. The jury of 12 men was sworn in and the body was viewed as required by law. It was then that the proceedings started to unravel, as Mr. Battye discovered that there were also newspaper reporters and two solicitors in the room. On the defensive from the very beginning, and being asked his name and position by the solicitor (Mr. Harmer) Mr. Battye refused to answer the questions. Then, pointing to the reporters, he said, "I suppose I shall see all this in black and white in the newspapers in a few days; but no-one has any business to be writing here ..." and then, "If Mr. Farrand was here, I am sure he would not allow one of you in the room." This exchange set the tone for the whole of the proceedings over the next 3 months. It's not the easiest task to condense all the witness testimony - the acrimonious exchanges - the bullying behaviour - the strenuous efforts to prevent anything getting out to the newspapers - and the points of law which Mr. Harmer frequently argued, in order to introduce his own witness statements. Harmer constantly hammered home the facts that the Meeting was a peaceful assembly, one that had been murderously dispersed in an illegal action, and that accountability lay with those in authority. On the 5th day of the inquest, September 29th, another person makes an unexpected appearance in the courtroom. This time it is a Manchester barrister, Mr. Ashworth, who walks in and interrupts proceedings. Both Mr. Harmer and the Coroner want to know whom he is representing, and his answer is, "the Town of Manchester" ie., the Magistrates. The inquest then continued ... witnesses called ... and frequent arguments between Mr. Harmer, the Coroner and Mr. Ashworth. Attempts to exclude the press were on-going, and there always seemed to be someone upsetting the coroner by taking notes. On the 9th of October the inquest was adjourned yet again ... and would never resume. In the following weeks, Mr. Harmer and his colleague, Mr. Dennison, requested the court to compel the Coroner to continue the inquest, without the frequent adjournments. An affidavit was presented in support of the motion, detailing the progress of the inquest and the obstructions they had encountered in conducting their inquiry. At first the Lord Chief Justice ruled in their favour but a challenge was mounted. On the Monday morning, Mr. Serjeant Cross undermined Mr.Harmer's statements and stressed the illegality of the inquest proceedings from the start. This was based on the technicality that the Coroner hadn't initially sworn in the jury, himself, and viewed the body with them, as required by law. He also stressed how the Coroner was put at a disadvantage by not being a solicitor himself and had turned to the magistrates and their own solicitor, purportedly in all innocence, in a desperate need for advice. On Wednesday the 1st of December, having heard nothing to the contrary, Mr.Harmer, with his assistant and witnesses, presented themselves at the Star Inn, Manchester, to continue the inquest. They were met at the door by Mr. Battye who informed Mr. Harmer of the Court's final decision ... the inquest would not continue - ruled null and void! Because Peterloo generated such strong reactions - from both sides of the political divide - it was referenced constantly, throughout the following years, and became a cornerstone of 19th century social and political history. Eventually, the longed for Reform Act of 1832 was enacted but it gave little to the working man - least of all a vote. It was in the years after this disappointment that the Chartist Movement came into being until crushed by the Government in 1848. The mass of published material from those early years of the 19th century is passionate ... accusatory ... and so many fearless of consequences ...

Opening Pages from the satirical publication, following Peterloo, 'The Political House that Jack Built' 1 F.A. Bruton, 'The Story of Peterloo' Pub. 1919; p. 30 Contributed by Sheila Goodyear |

||