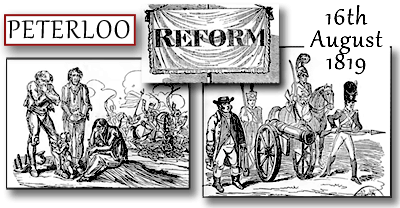

The Peterloo Massacre - Manchester 16th August 1819

TRANSCRIPTION OF : 'NOTES & OBSERVATIONS, Critical & Explanatory, on the Papers Relative to Page 161-166 A REPLY, I have noticed, in my remarks on the parliamentary documents, the design attributed to the Radicals of making a general division of property among themselves. And Mr. Philips is not behind hand with Lord, Sidmouth's correspondents, in ringing in our ears this extravagant and silly calumny, He says (page 9,) "So confident of success had they become, that their insolence was insuiferable; a. general division of property, and a termination of all taxation, were considered inevitable; silver was rapidly disappearing from circulation, and many instances occurred of rents being purposely withheld, under the expectation that a revolution would cancel all such obligations. The consternation that prevailed was indescribable." And again, (page 48) "There was not an estate nor a dwelling·place, in their line of march, that had not been parcelled out in their imaginations to themselves; the division of property they considered certain; and the principal part of them expected the accomplishment of their wishes on that very day." The common rules of justice require evidence to support any charge, but the new system of ethics of which Mr. Francis Philips seems to be one of the patrons, disdains to be bound by the vulgar trammels of natural equity. In proportion as the proof of crime is deficient, are the accusations of it more loudly bellowed ; - in proportion as the people remain peaceable, are they charged with a disposition to be tumultuous. For, as these calumniators of the most useful and most numerous class of their countrymen, cannot convict by their proofs of guilt, they endeavour to confound by their enormity of accusation. They take the vulgar proverb as THEIR rule of conduct,

whilst their happy knack at generalization preserves them from the inconvenience of being individually called upon to prove the truth of the charges they bring forward. But does Mr. Philips really flatter himself, that there is any individual in the country, dolt or idiot enough to believe such an accusation, so supported? I mean not to insinuate a doubt of Mr. Philips's personal veracity; but does he really believe, that any evidence which he could furnish, would suffice in a court of justice, to convict any individual of the offence of inculcating such dangerous and treasonable notions? If he can furnish such sufficient evidence against persons so offending, why has he not done it already? lf he cannot, the charges he has brought against the great body of the labouring classes, he may reconcile to his conscience as he can. If I were disposed to imitate him, I might take all his assertions in rotation, and meet them by a direct negative; but I shall content myself here with saying, that with considerable means of estimating the intelligence, and judging of the dispositions of the people, no one fact has ever come under my personal knowledge, which can give the slightest sanction to Mr. Philips's opinions or statements. And with respect to the consternation which he affirms to have existed, however individuals may have alarmed themselves, it certainly was not general, or even common. There was no open and public manifestation of it; and "de non apparentibus et de non existentibus eadem est ratio." Mr. Philips's assertion, (page 2) that "seasons of adversity are most congenial to the machinations of the disaffected; on such occasions only can they succeed in distributing their noxious poison," is quite contradictory of his statement, (page 7,) that "a very great proportion of the labonring classes were never better off, except as to politics and religion, than at the present time." It is not for me to attempt to reconcile his contradictions. With respect, however, to the situation of the weavers, who are the most numerous class of our population connected with the cotton trade, it is to be observed, that though, perhaps, their wages may now be somewhat higher than they have heretofore at times been, yet as those periods of depression, when- wages were lower, have always been shorter in their duration than the present, the distress of the weavers, probably, never was so great as now. This will be rendered pretty evident when I state, that the result of an inquiry into the earnings of weavers, in all the diiferent branches of our cotton manufacture, does not present a general average, taken for a long period, of 8s. per week. But supposing the wages of the weavers to be adequate to obtain for them a comfortable subsistence, does Mr. Philips think that therefore they would or ought to cease to be friends of reform ? Does he take no account of the general spread of political information amongst the labouring classes? Does he think they can be now taught to forget that they have political rights to claim, as well as political duties to fulfil? Does he think they can be persuaded to leave politics to "their betters," to the "higher orders?" that the experience of the last thirty years is to be lost upon them? that they are to be utterly listless and unconcerned on subjects on which the sufferings or the comforts of their lives mainly depend? that those whose favourite political measures have entailed upon the- country that burthen, which it is scarcely within the limits of possibility she shall much longer continue to sustain - that they are still to be held entitled to public confidence - still to guide public opinion, or to decide public measures? If Mr. Philips be so heedless of the lessons of experience, so regardless of the signs of the times, I have only to pray, that the respectable, middle, and more affluent classes, may not generally be partakers in his errors or miscalculations. The tone and temper of Mr. Philips's remarks, with respect to the manner and appearance of the people, on their way to and at the meeting, deserve a few observations. He says, (page 2l,) "One man particularly attracted my notice, from his audacious appearance; having on his shoulder a club, as thick as the wrist, rough, newly cut, with the bark on, and many knots projecting. My eye being directed towards him, he shook his club at me in a menacing manner." Though I have no doubt, that Mr. Philips thinks his estimation of the character and views of the reformers is the correct one, I am equally certain, that the public will agree with me, that if he do err, it is not on the favourable or candid side; in as much as there are few crimes which can be contemplated or committed by a large body of persons, that he has not laid to their charge. I therefore cannot help thinking, either that there is a little unconscious colouring in the above description, or, what is more probable, that Mr. Philips had assaulted the fellow, by the expression of his countenance, before the latter returned the compliment, by the shaking of his club; particularly as Mr. Philips admits, that "when he mixed with the crowd," even near the Hustings, "no direct affront was offered him." Mr. Philips's account of the meeting itself is very short, and does not contain much, except in the way of inference or supposition, to which.it is possible to object. The regularity of approach to St. Peter's, the marching in military array *1 (if it must be called so,) but which I could only recognize as the adoption of that plan of proceeding to the place of meeting, which was the farthest removed from any thing having at all the appearance of tumult; the flags, the music, the sticks, are all, with some minor differences of detail, characteristics, the exhibition of which, at the meeting, is admitted by everyone. With respect to the sticks: I saw a column pass down Mosley Street, (I do not know whether it was the same that Mr. Philips had seen at Ardwick, though, from the route by which it came upon the ground, that is not improbable.) Of the persons who composed it, however, I calculated at the time, that about one in ten, certainly not two in ten, had sticks; and I only saw one, which, from its appearance of freshness, seemed to have been provided specially for the occasion. I did not observe any which, according to the sagacious conclusion of Mr. Wheeler, were "shouldered as representative of muskets;" nor if I had, should I have considered it as of importance, any more than if they had been bestrode, "as representative of" horses. The friends of alarm, knowing that "walking stick" is not a term which would excite much terror, endeavour to make the formidable weapons of the weavers appear more fearful, by calling them "clubs and bludgeons." They were, however, nothing but common walking-sticks; and indeed I was much surprised to see so few even of them, for every one at all conversant with the habits of country·people hereabouts knows, that when they have far to walk, they seldom omit taking one with them. To my view, the whole manner and appearance of the people, and I saw most of the different bodies, shewed that they attached a degree of serious importance to the business, about which they were assembled. That their objects and intentions were peaceable, was proved to demonstration, by their bringing with them to the meeting, so many women and children; nor did I see an action, or hear a word, in the slightest degree obnoxious to the laws of the land. None, indeed, of the most bitter opponents of the meeting, none of the most anxious or the most acute defenders of the magistrates, have yet ventured to assert, that any the slightest act of violence had taken place before the charge of the cavalry. All that Mr. Hay could express at the time, was a conviction that the meeting "bore the appearance of insurrection." , All that Mr. Francis Philips yet alleges, is a conviction of its "revolutionary tendency." In this state of perfect peace and quietness the assembly still continued; when the yeomanry cavalry came very rapidly upon the ground. The speed of their progress was such, even at some distance from the field, that a woman was knocked down, her child fell from her arms and was killed ;*2 an old man, considerably upwards of seventy years of age, was rode over, and both his arms were broken, as they turned the corner of the cottage wall. In describing the advance of the cavalry towards the hustings, Mr. Philips says, he "did not see a sword used." I am not aware that any person has ever asserted that he did. He " solemnly believes, that had the crowd given way to them, (the yeomanry,) no cuts would have been given." Footnotes~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ *2. "Since this passage was written, an affidavit has appeared in Mr. Joseph Aston's paper, to prove that this child was not sabred. Mr. Philips also says, "it was said, that the child was sabred." I invite either Mr. Aston or Mr. Philips, to prove that this child was ever said to have been sabred, or to shew any probable ground for their assertion, that the real cause of its death was in any respect misrepresented. So far from it, the name of the yeoman, by whom its mother was rode down, is and long has been known; but as the circumstance was purely accidental it has been carefully kept back. ***************************************************************

'NOTES & OBSERVATIONS, Critical & Explanatory, on the Papers Relative to the Internal State of the Country, Recently Presented to Parliament; to which is appended, a REPLY to Mr. Francis Philips's 'Exposure of the Calumnies circulated by the Enemies of Social Order ...' Transcribed by Sheila Goodyear 2019 LINK to full .pdf document of 'Notes & Observations ...'

on the Internet Archive website to read or download. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||