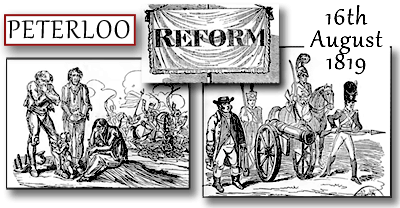

The Peterloo Massacre - Manchester 16th August 1819

TRANSCRIPTION OF : 'NOTES & OBSERVATIONS, Critical & Explanatory, on the Papers Relative to Page 189-195 A REPLY, The following hand-bill was also partially posted, butsoon afterward it was rapidly pulled from the walls. "Manchester, August 17th, 1819. The Boroughreeves and Constables of Manchester and Salford do hereby caution all the inhabitants to close their houses, shops, and warehouses, and to keep themselves and all persons under their controul within doors, otherwise their lives will be in danger. Carts and all other carriages must be instantly moved from the streets, and other public roads." In the report of the approach of pikemen, which caused this intimation, and which completely put a stop to businessfor that day, besides creating very considerable alarm, and subjecting persons of true constitutional feeling to the unpleasant sensations arising from the parading of military about the town, and from seeing artillery planted at the bottom of one of our most frequented streets, - there was not one syllable of truth *1. There are persons who have conjectured that conscience had something to do with the apprehensions exhibited upon the occasion, in asmuch as that certain parties could not disguise from themselves what they deserved to suffer that day, for what they had done the day before. The opinion of the country has been so strongly expressed with respect to the treatment experienced by Mr. Hunt and his fellow prisoners on their examination, contrasted with the indulgencies which extended towards Meagher, that it is useless for me to enlarge upon that subject. Nor shall I do more than just notice the petty spite of sending Mr. Hunt off to Lancaster immediately after his examination was closed, when it has been promised that bail should be taken any time that evening, and notice of bail had been accordingly given. When, by the ignoring of the bills presented at Lancaster, and by the refusal of the Manchester Magistrates to grant warrants against members of the yeornanry respecting whom charges were laid before them, it was rendered almost doubtful, whether any means would offer, by which the whole question respecting the peaceable demeanour of the meeting of the 16th of August - its legality, and the unlawfulness of the manner in which it was dispersed, - might be brought before the country upon oath, the death ofJohn Lees took place at Oldham. The summoning of the Jury was in the usual form, though perhaps, from its having been done in the first instance by the coroner's clerk, it might have been considered irregular in that respect, had not the jury been sworn by the coroner personally before the examination of the witnesses commenced. At the outset ofthe business, the coroner made great professions of independence, the emptiness of which was, however, very soon demonstrated. Indeed, from Mr. JOSEPH DOWLING'S short-hand notes of the proceedings at the inquest, the country will be very well able to decide, whether his conduct had any resemblance whatever to the upright and rigid impartiality of a judge. Mr. Philips's promise to "restrain his investigation," with respect to the proceedings at Oldham, (page 49) is not perfectly in keeping with the next line but one, where he says, "never was there such a mockery of evidence - never was a solemn court profaned by such abuse." This was pretty well, whilst the inquest was still pending; but now that it is wholly nullified, it might not be amiss if Mr. Philips would enlighten the public by shewing the grounds upon which he has made these assertions, unless, indeed, they are to be taken as "Vox et preterea nihil," - phrases, put in to construct a good sonorous sentence. Mr. Philips surely cannot deny that, in order to determine the quality of the act by which Lees met his death, it was necessary to ascertain the character of the meeting, to prove that, it was legally and peaceably assembled, and therefore wholly under the protection of the law. This being taken to be established by proof, it then follows, that the meeting was violently and illegally assaulted; and Lees being, by medical testimony, stated to have met his death, in consequence of wounds which he was proved to have received, in the course of this attack upon the meeting; and it being impossible to ascertain by what individual the wounds were inflicted; it follows, according to law, (though probably not according to Mr. Philips,) that inquiry must be taken respecting all the persons engaged and co-operating in that illegal procedure, in consequence of which Lees met his death. For, if a number of persons in concert do an unlawful act, in the course of which one of them inflicts a wound which causes the death of an individual, they are by law all equally guilty of the crime of murder. Upon this point it may not be improper to give the authorities: Plowden's Commentaries, vol. 1 , page 97-8 ; "All the other justices, (that is, except Bromley,) after advising thereof for two days, held clearly, that they might proceed with the prisoner at the bar, without any inconvenience arising from it. For they said, that when .many come to do an act, and only one does it, and the others are present abetting him, or ready to aid him in the fact, they are principals to all intents, as much as he that does the fact: for the presence of the others is a terror to him that is assaulted, so that he dare not defend himself. - And then, in as much as both together, viz. the wounds, and the presence of others, who gave no wounds at all, are adjudged the cause of his death, it follows, that all of them, viz. those that strike, and the rest that are present, are in equal degree, and each partakes of the deeds of the other. And notwithstanding there is but one wound given by one only, yet it shall he adjudged by law the wound of every one; that is, it shall be looked upon as given by him, who gave it by himself, and given by the rest by him as their minister and instrument. And it is as much the deed of the others, as if they had all jointly holden with their hands the club or other instrument with which the wound was given, and as they had altogether struck the person that was killed." 1 Hale, 437-8; " If several are indicted, A as giving the mortal blow, and the others as present, aiding, &c. evidence that one of the others gave the blow, and that A only was present, &c. will maintain the indictment." 1 East. P. C. 350 ; "So also if the evidence be, that J S, not named in the indictment, or even that a person unknown gave the blow, and that A, B, and C, named therein, were present, aiding and abetting." But amid all the strange ebullitions of party feeling, amid all the rancorous invectives of political opposition, I did yet expect to have seen such, a degree of public decency maintained, as would have prevented an inquiry so solemn and so important, in every point of view, as that which came before the Coroner's Jury at Oldham, from being spoken of as a "farce." What, is the death of any individual, under any circumstances, a "farce?" When that death is obviously by violence, is the cause not to be inquired into? And still more, when that violence has been accompanied by circumstances without parallel in the modern annals of British history, circumstances into which this whole nation has promptly and unitedly called for investigation, are those who endeavour personally to obtain it, to be assailed by obloquy and re- proach? Mr. Philips says, "we have not a shadow of just complaint against any of the Magistrates, the constables, and military." We say we have, and state the grounds of our assertion. Mr. Philips says, they are "slanderous falsehoods, circulated by the vilest of the vile." Here there is assertion against assertion, and where statements so directly oppose each other, how, in God's name, are we to get at the truth, except by evidence in a court of justice, given upon oath? If Mr. Philips's clients be so confident of their innocence, they ought to be most anxious for inquiry; their friends, indeed, say they are so; but I heard little of this anxiety whilst the Oldham inquest continued. I can only conclude, that it is now loudly expressed, because it is known to be unattainable. Where indeed are the sufferers of the 16th of August, now to look for redress? What avenue of public justice now remains open to them? By what course are they to bring the tale of their sufferings - to exhibit the nature of their wounds, before a jury of their country? Had an "audacious" radical trod on Mr. Philips's toe, there would have been no difliculty in bringing him to punishment; but, into a scene of military execution, in consequence of which ten persons at least have lost their lives, and nearly six hundred have been wounded, even inquiry cannot be obtained. Perhaps, however, I may here have gone too far. Most happy indeed shall I be to find it so. For I am thoroughly convinced, that the existing dissatisfaction can never be wholly removed, until the poor have regained that perfect confidence in the impartiality of the law - that feeling of individual security derived from its protecting influence, of which recent events have unquestionably deprived them, That this confidence should have been destroyed, deplorable as is the fact, cannot excite surprise. All to whom the proceedings of our local, and indeed of our higher courts, for the last four months, have been familiar, must have been painfully impressed with the conviction, that though the law is no respecter of persons, those to whom the administration of it is committed, are not always equally unbiassed. In presuming however that this conviction would be painful to all, I know that I have erred. There are persons in influential stations amongst us, who in my presence have spoken of the poor as "thieves," and of those who have laboured to assist them in obtaining justice, as "scoundrels." But to such I do not write. They are where I wish them to remain - in the ranks of my political opponents. I write to those only who are anxious that the impartiality of the law, like the chastity of Caesar's wife, should not even be suspected. I do not ask - l have never wished, to exempt the conduct of the reformers from the scrutiny and supervision of the law; but whilst I would make that law the punisher of their crimes, I would make it also the protector of their rights, and the avenger of the wrongs they suffer. lf indeed, there be any class whose failings should be mercifully visited, and whose rights should be scrupulously upheld, that class is the poor: they are exposed to peculiar temptations, and they are most likely to err through ignorance on one hand, whilst on the other they are least able to protect themselves. In the constitution of civil society, our duties are co-existent with our rights. When we resign part of that liberty to which in a state of nature we are entitled, it is for the purpose of being more effectually secured in the enjoyment of the portion which we retain. We give up the right of retaliating the injuries we receive, only upon the condition that the law will avenge them for us. And if this be not done, if we suffer and the law afford us no redress, the implied contract by which society subsists is directly infringed, if not wholly abrogated. lt is to the deductions from this reasoning, just though it be, that I look with the greatest apprehension, as connected with the dispersion of the Manchester meeting. The radicals have long been accused, God knows with how little truth, of a disposition to assassination. But what is so likely to create this disposition - what so likely to stimulate them to personal revenge, as the feeling that they are not protected by the law? lf the law not only will not punish those who injure them, but will not inquire into their complaints against those by whom they consider themselves to have been injured, should we have any right to be surprised at their taking the infliction of punishment upon themselves? Is not the fact that they have not done this, a conclusive reply to all the slanders against them? And is it not infinitely more desirable that punishment, wherever it be deserved, should follow the cool and temperate investigation, and the just and impartial decision of the law, than that it should be inflicted upon the mere determination, and according to the private estimate, of those who fancy themselves injured? This last sentence applies absolutety to the conduct of the Magistrates and yeomanry on the 16th August, whilst fortunately its reference to the people is hitherto only hypothetical. If any of the people, on the 16th August, committed any crime—- if there were any cause for complaint against them, it would have been right to take them into custody for the purpose of bringing them to trial; but it was not right upon a mere private and capricious interpretation of circumstances and their tendency, - without trial - without legal proof of guilt, to subject the whole mass to the danger of military execution. Why do men ever assassinate, but because they dare not kill openly? And if because they dare do it, they do kill by open violence, in what respect is the act less criminal than private assassination? Footnotes~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ***************************************************************

'NOTES & OBSERVATIONS, Critical & Explanatory, on the Papers Relative to the Internal State of the Country, Recently Presented to Parliament; to which is appended, a REPLY to Mr. Francis Philips's 'Exposure of the Calumnies circulated by the Enemies of Social Order ...' Transcribed by Sheila Goodyear 2019 LINK to full .pdf document of 'Notes & Observations ...'

on the Internet Archive website to read or download. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||